Right after I turned twelve years old I wrote a novel. That’s honestly not a brag. I didn’t write On the Road With Snicklefritz because I was some kind of literary prodigy. I wrote it because living with my family left me desperate to be heard and understood.

Does anyone ever write for any other reason than to be heard and understood?

Thank God I’ve gotten over that phase of my life.

Moving on, I am confident that the only thing that kept On the Road With Snicklefritz from sweeping all the major book awards was that nobody read it.

“What matters is that this means something to you,” said my mother, gently pushing my novel back toward me. “Having others read it can only diminish that meaning. You keep this close to your heart, sweetie. It’s yours, and no one else’s.”

“Do I want to read your novel?” asked my dad. “Do I look like I have nothing better to do than waste my time on what you’ve been wasting your time doing?”

Wasn’t crazy about the sentiment, of course. But definitely registered the wordplay.

You get your nourishment where you can.

But cute wordplay wasn’t going to be enough for me at this particular moment.

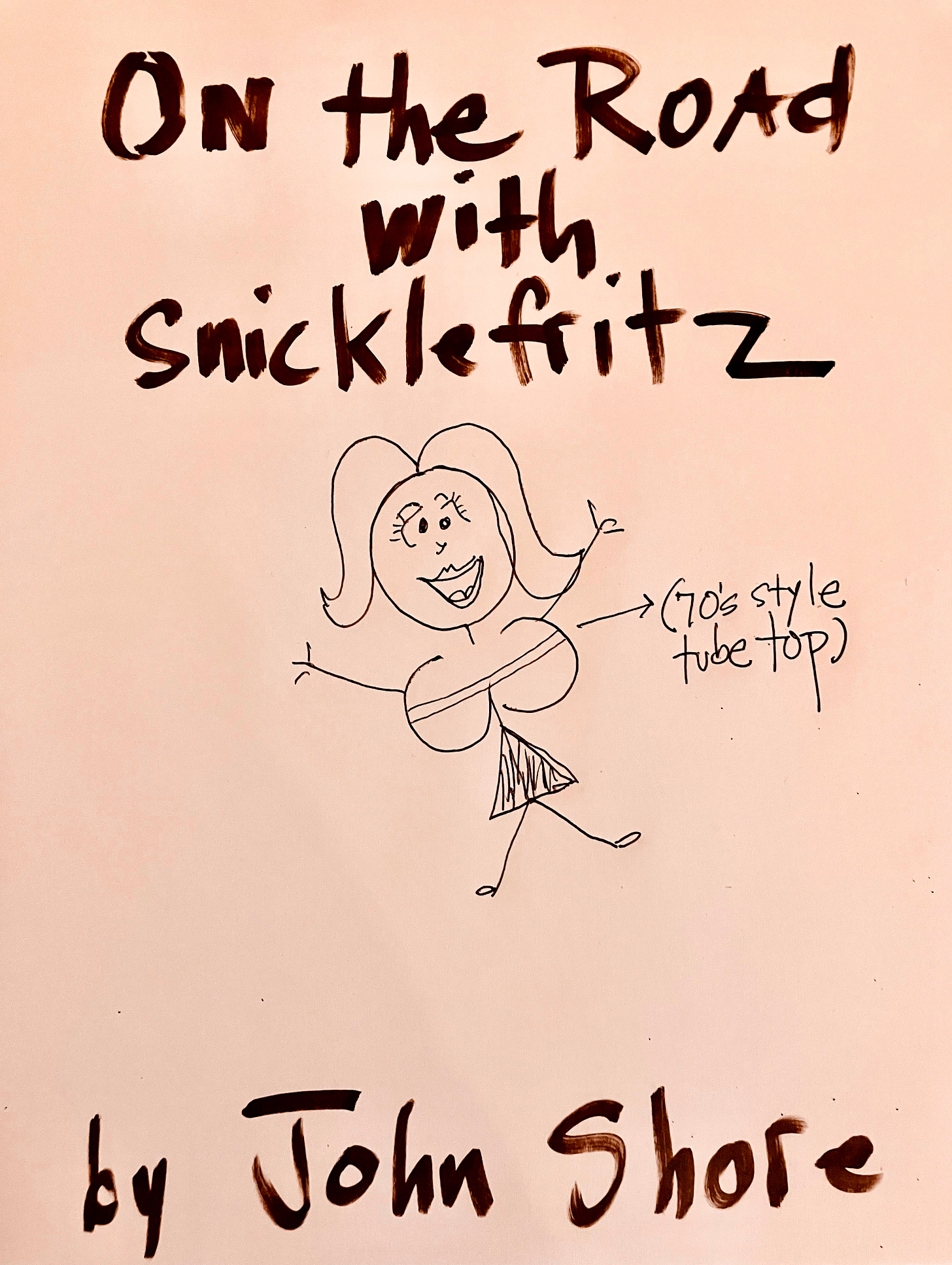

“Oh come on, Dad!” I said, waving my actual manuscript at him. “You can’t read this? What don’t you read? Nobody reads like you. You bring home a whole grocery bag full of paperbacks from the library every Sunday night. You keep a novel in the living room, one in your office, one by the side of your bed, one in your bathroom, one probably in your car for when you’re stuck in traffic. But you can’t read mine? What if I put a picture of a half-naked woman on the cover? Then would you read it?”

After staring blankly at me for a long moment, my dad, “Are you through?”

“Yes.”

“Good,” he said, stepping around me and heading off to wherever it was he went some nights.

Could have been worse. He could have hit me. But he never, ever did that—a fact for which I was always grateful, because just about all my friends’ dads regularly hit them, some horribly. My dad was six-foot-four, and insanely strong. So I knew that if he ever did hit me, he’d kill me. And he knew that too, of course. And he knew that I knew that. And I knew that he knew that I knew that. And he knew that I knew that he knew that I knew that. And I knew that he knew that I knew that he knew that I knew that.

Wait. Knew. Knew. KNEW.

That’s how you spell that, right?

Is that even a real word?

KNEW.

Isn’t it some kind of giant Australian bird? Or maybe the call letters for a radio station?

That’s what it should be. KNEW, Talk Radio.Tell us what’s new in YOUR life!

It’d just be people calling in all day to tell about something new in their life: their new kitchen mitts, their new next-door neighbors, their new discovery that they’re sexually excited by termite shavings. You’d never know what somebody’s next new thing would be!

So you keep listening! I know I would.

Sure as heck beats listening to another true crime podcast. Enough of those already. We get it: a sociopathic asshole killed someone. Let’s move on.

To KNEW: What’s New With You?

You’re welcome, radio world.

But . . . um . . . yeah.

Anyway.

Where the fuck was I?

Oh, right: my dad never hit me—an awesome record of restraint, because, you know, it’s me. Even better was that, emotional cretin or not, the man was funny. It wasn’t exactly his love language, but my dad definitely spoke pure Long Island sarcasm. (He grew up in New York.) And thus, in order to in any way communicate with him, did I also become sarcastic and funny and . . . well, bitterly cynical.

Because you know what they say: If you can’t beat ‘em, and you can’t join ‘em because they won’t let you, try to at least make ‘em laugh so that one day you don’t inadvertently piss ‘em off and they backhand you straight into an early grave.

My dad almost laughed at my half-naked lady cover joke, by the way. I saw it as he passed by me. And who’s to say my stick figure with a flip hairdo and ridiculously huge round boobs wouldn’t have pulled him in?

Most of the paperbacks he brought home from the library did feature on their cover a beautiful, cleavage-forward woman looking like she wanted to be, recently had been, or was very soon to be ravished. In those days (late-sixties, early seventies) images of hot lustful babes were everywhere you looked: book covers, movie posters, TV commercials, magazine ads, bill boards, album covers . . . back then (and way before, I know) all advertisers seemed to agree that the surest route to a person’s wallet was through their crotch.

Boy, it sure is great that as a culture we’ve moved past that kind of fundamentally misogynistic shallowness, isn’t it?

See? Sarcasm! I still got it!

And there was plenty of it in On the Road With Snicklefritz, too. (Segue score sort of!) On the Road was a rollickingly mesmerizing story of a twelve-year-old boy, James, who runs away from home with his faithful pet/sidekick, a tabby cat named Snicklefritz.

“C’mon, Snicklefritz,” said James. “Let’s blow this joint.”

“‘Blow this joint’”? said Snicklefritz. “You watch too much TV.”

That was the intriguing thing about Snicklefritz: he could talk. But he would only talk to James, and only when the two of them were alone together. That last part drove James bonkers.

“We’re out here scrounging around in dumpsters for food,” complained James. “When you’re a talking cat! We could make a fortune off you!”

“We’re not scrounging around in dumpsters,” said Snicklefritz.

“Well, we will be, once we run out of the money I made washing cars.”

“And I don’t know if we could make a fortune,” Snicklefritz continued.

“We definitely could.”

“No—I could make a fortune. Remind me again of why I would need you to do that?”

It took James a moment. “Wow,” he said. “Even for a cat, you have a rough tongue. Maybe it is best that you don’t talk to anyone but me.”

But sometimes James sure did wish that Snicklefritz would say something.

“Come on, Snick,” James urged the cat while their waitress, pen and pad in hand, patiently waited by their booth at the roadside cafe they’d stopped at for an early lunch on their very first day running away from home. “Tell the waitress what you want.”

But Snicklefritz only stared at James with that, “I’m a cat; you’re not; I see how you suffer because of that; I don’t care” look.

James laughed nervously at the waitress. “He talks, he really does.”

“I’m sure he does, sweetie,” said the waitress. To Snicklefritz she said, “Don’t you look so cute, with your napkin all tucked into your collar. So classy! [I used to think fancy people tucked napkins into their shirt collars when they dined out.] We have tuna salad, sugar-whiskers. Would you like some of that? Or how ‘bout some clam chowder? The chowder here’s real good.”

Not for a moment while she was talking did Snicklefritz take his big green eyes off of James.

“C’mon, Snickles,” James whispered semi-maniacally due to his growing embarrassment. “Order something. You know you want that chowder.”

But Snicklefritz, in his Snicklefritzy way, stuck with the pretension that he could no sooner speak than he could hold a soup spoon.

Finally James turned to the waitress. “He’ll have the chowder. And could you pour a little milk in it, please, so it won’t be too hot?”

After their lunch James and Snicklefritz enjoyed a big day full of big adventures. They walked to a nearby reservoir, where they did a little fishing.

“Watch how it’s done,” said Snicklefritz. With lightening speed he darted his paw into the lake and pulled out an actual fish he’d hooked with his claws.

“Holy cow!” said James. “Why am I using this dumb stick with a string on it?”

“Mphmmpfff,” said Snicklefritz, his mouth already too full to talk.

A little later that day they came across—and snuck into—a carnival. But Snicklefritz was too short to go on any of the rides.

“Let’s see if they’ll at least let you on the merry-go-round,” said James.

“Let’s not,” said Snicklefritz. “Going around and around in a circle while the dumbest music in the world plays is really more of a human thing.”

Later in the afternoon they went to the movies. Snicklefritz sniffed his box of popcorn, looked up at James, and whispered, “This isn’t real butter.”

James whispered back, “But it’s delicious, right?”

“Wrong,” said Snicklefritz. “Go get me hot dog. Plain. No bun.”

Toward the very end of the day they even hopped a train. Well, Snicklefritz did. As the endless succession of railroad cars slowly rolled by them, James saw an empty one, its doors wide open.

“C’mon!” said James, swooping Snicklefritz up into his arms. “We can make it!” He ran and ran, as fast as he could, and finally got close enough to the open car to toss Snicklefritz inside of it.

But by then James was more exhausted than he realized he’d be. He was slowing down—or the train was speeding up. Either way Snicklefritz was slowly but surely pulling farther away from him.

For his part, Snicklefritz was sitting at the edge of the rattling car, watching as James ran, stumbled, and ran toward him again. At a moment when James was crying out for him, his outstretched hand desperately grabbing nothing but air, Snickefritz turned away, and with a flick of his tail strolled back into the darkness of the car.

Finally, having no choice, James ceased running. He collapsed onto the dead brown grass by the side of the tracks.

He could barely catch his breath. He didn’t know what to do.

He let himself drop down onto his side, and then rolled over onto his back. He felt his heartbeat slowing down. After a bit he positioned himself so that the back of his head was resting on the train track. The rail’s cold hard steel hardly made for a fluffy pillow. But James held his position, pain or not. Because he knew that soon enough he would spot a star light, star bright, first star he saw that night. And when that happened he was going to wish upon that star so hard that it would be impossible for whatever force was behind it—for whatever power was supporting that star, and all the stars, and everything else in the whole entire universe—to continue to ignore him or his wish.

My Substack is free for all. If you’d like to support my work here, buy me a coffee! Thanks!

Excellent read, as always.

I wish I saved the cartoons you sent me in 6th grade class.